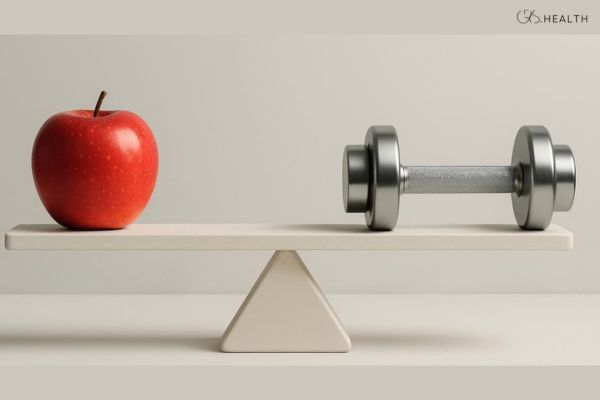

The Calories In, Calories Out diet—also known as CICO—is one of the most popular and debated methods for weight loss. At its core, the principle is straightforward: if you consume fewer calories than your body burns, you will lose weight. If you consume more, you will gain weight. This concept is deeply rooted in the laws of thermodynamics, but when applied to the complexity of human physiology, many layers and factors come into play.

In this complete guide, we will explore the science behind the Calories In, Calories Out diet, its benefits, drawbacks, and how to implement it safely. We will also discuss the common myths, practical tips, and who should be cautious with this approach.

What Is the Calories In, Calories Out Diet?

The Calories In, Calories Out diet is based on the principle of energy balance. Calories are units of energy that come from the food and beverages we consume. The body requires energy to perform essential functions such as breathing, circulating blood, digesting food, repairing cells, and supporting physical activity.

- Calories In refers to all the energy consumed through food and drinks.

- Calories Out refers to the energy the body uses through metabolism, physical activity, digestion, and other daily functions.

When calories in exceed calories out, weight gain occurs. When calories in are less than calories out, weight loss happens. When both are equal, weight maintenance is achieved. This is the fundamental principle of the Calories In, Calories Out diet.

How the Calories In, Calories Out Diet Works

Energy Balance and Metabolism

The Calories In, Calories Out diet works on the concept of energy balance. Your body’s daily energy expenditure can be broken into several key components:

- Basal Metabolic Rate (BMR): The energy required to keep the body alive at rest, such as maintaining heartbeat, breathing, and cell repair.

- Thermic Effect of Food (TEF): The energy used in digesting, absorbing, and metabolizing nutrients. Protein typically requires more energy to process than carbohydrates or fats.

- Physical Activity: Calories burned during exercise and movement.

- Non-Exercise Activity Thermogenesis (NEAT): The energy expended through daily activities not classified as exercise, such as walking, fidgeting, or standing.

Adaptations and Complexities

While the theory is simple, the body adapts to changes in energy intake:

- As you lose weight, your total energy expenditure often decreases because you have less body mass and your metabolism may slow down.

- Hormonal changes affect appetite and satiety. For example, ghrelin levels (the hunger hormone) may rise, making you feel hungrier.

- Individual factors such as age, sex, genetics, body composition, sleep quality, and stress levels also affect how efficiently your body burns calories.

These complexities explain why two people on the same Calories In, Calories Out diet may not experience the same results.

Benefits of the Calories In, Calories Out Diet

The Calories In, Calories Out diet has several potential advantages:

- Simplicity and Flexibility

Unlike diets that restrict certain food groups, this method allows you to eat a wide variety of foods, as long as you stay within your calorie target. - Scientific Backing

Numerous studies confirm that calorie deficits lead to weight loss regardless of whether the diet is low-fat, low-carb, or high-protein. - Awareness of Eating Habits

Tracking calories can help individuals become more conscious of portion sizes and hidden sources of calories, leading to better long-term eating habits. - Adaptable to Different Lifestyles

Since there are no forbidden foods, the Calories In, Calories Out diet can be adjusted to suit different cultural preferences and lifestyles.

Drawbacks and Criticisms

Despite its benefits, the Calories In, Calories Out diet has limitations:

- Nutritional Quality May Be Overlooked

People may focus only on staying within a calorie goal while consuming processed, nutrient-poor foods. This can lead to deficiencies and poor health outcomes. - Difficult to Sustain

Constantly tracking and restricting calories can be mentally exhausting. Many people find it hard to maintain in the long term. - Risk of Obsessive Behavior

Strict calorie counting can trigger unhealthy relationships with food and may contribute to disordered eating. - Individual Variability

The same calorie intake may produce different results for different individuals because of variations in metabolism, hormones, and activity levels.

How to Follow the Calories In, Calories Out Diet

Step 1: Estimate Your Daily Energy Needs

You can calculate your Basal Metabolic Rate using equations such as Mifflin-St Jeor or Harris-Benedict, then multiply by an activity factor to determine your Total Daily Energy Expenditure (TDEE).

Step 2: Set a Calorie Goal

For weight loss, aim for a moderate deficit of about 250 to 500 calories per day. Larger deficits may produce faster results but often lead to fatigue, nutrient deficiencies, and rebound weight gain.

Step 3: Prioritize Nutrient-Dense Foods

Focusing on whole, minimally processed foods helps keep you satisfied while ensuring adequate vitamins, minerals, and fiber. Vegetables, fruits, lean proteins, whole grains, and healthy fats should make up the majority of your diet.

Step 4: Monitor Progress

Track your calorie intake and monitor changes in weight or body composition. Make small adjustments if progress slows.

Step 5: Support With Lifestyle Factors

Adequate sleep, stress management, hydration, and regular physical activity, particularly strength training, can all support better results and help preserve muscle mass.

Research and Evidence

Research consistently shows that weight loss occurs when calorie intake is lower than calorie expenditure. Controlled feeding studies have demonstrated that when total calorie intake is matched, weight loss results are similar across low-carb, low-fat, or other macronutrient-focused diets.

However, studies also reveal that most people underestimate how much they eat and overestimate how many calories they burn. This highlights the challenge of applying the Calories In, Calories Out diet in real-world conditions.

Meta-analyses further suggest that calorie restriction over extended periods leads to significant weight loss, but sustainability is often the biggest barrier. Long-term adherence and lifestyle changes are key for maintaining weight loss.

Common Myths About the Calories In, Calories Out Diet

One widespread misconception is that all calories are equal. While a calorie is a measure of energy, the body responds differently depending on the nutrient source. For example, 200 calories of sugary snacks may be digested quickly and fail to keep you full, while 200 calories of protein-rich food may increase satiety and burn more energy during digestion.

Another myth is that you can eat whatever you like as long as you stay under your calorie target. While technically true for weight loss, ignoring nutrient quality can lead to poor health, low energy, and nutritional deficiencies.

A third myth is that more exercise always guarantees more weight loss. In reality, excessive exercise can lead to fatigue and compensation through increased appetite or reduced daily activity.

Finally, some people assume that once they reach their goal weight, they can return to old habits. Without mindful maintenance, the energy balance will shift again, leading to weight regain.

Who Should Be Cautious With the CICO Diet

While the Calories In, Calories Out diet can be effective, it is not suitable for everyone. Children and adolescents, pregnant or breastfeeding women, and people with medical conditions affecting metabolism may require higher calorie intakes or specialized nutrition.

Those with a history of eating disorders or individuals prone to obsessive behavior around food may find calorie tracking harmful. In such cases, professional guidance is essential.

Practical Example of the Calories In, Calories Out Diet

Imagine an individual with a total daily energy expenditure of about 2,500 calories. To lose weight, they might set a target of 2,000 calories per day. A day of eating could look like this:

- Breakfast: oatmeal with fruit and nuts

- Lunch: grilled chicken, quinoa, and vegetables

- Snack: Greek yogurt with berries

- Dinner: baked salmon with sweet potato and spinach

They may also incorporate moderate physical activity such as brisk walking, cycling, or resistance training several times per week. Over time, they would monitor their progress and adjust their intake as needed.

Conclusion

The Calories In, Calories Out diet is built on a scientifically sound principle: energy balance. It is simple, flexible, and supported by research as an effective way to lose weight. However, it is not without challenges. Nutrient quality, metabolic adaptations, individual variability, and psychological factors all influence success.

For most people, the best results come from combining calorie awareness with a focus on whole foods, adequate sleep, regular activity, and sustainable lifestyle habits. With mindful application, the Calories In, Calories Out diet can be a powerful tool for achieving and maintaining a healthy weight.

Sources

- MyFitnessPal, 8 Myths About the CICO Diet

- BioMed Central, Comparing caloric restriction regimens for effective weight management in adults: a systematic review and network meta-analysis

- MDPI, Is Fasting Superior to Continuous Caloric Restriction for Weight Loss and Metabolic Outcomes in Obese Adults? A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Clinical Trials

- The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, Energy balance and its components: implications for body weight regulation