A high white blood cell count (also called leukocytosis) is one of the most common findings in routine blood tests. It often signals that your immune system is active — fighting infection, inflammation, or another stressor. However, in certain cases, it can also indicate a more serious medical condition, such as a bone marrow or blood disorder.

White blood cells (WBCs) play a central role in defending the body from infectious agents and abnormal cells. Understanding what causes a high white blood cell count and how to interpret it correctly helps distinguish normal immune activity from disease-related conditions.

What Is a High White Blood Cell Count?

White blood cells are immune cells produced in the bone marrow. A high white blood cell count refers to an increased number of these cells circulating in the bloodstream.

In most adults, a WBC count above 11,000 cells per microliter (µL) is considered elevated. However, normal ranges vary depending on the laboratory, age, sex, and physiological status. For example, pregnant individuals may have higher baseline counts without any disease.

When a laboratory report indicates leukocytosis, doctors also look at which type of white blood cell is elevated — neutrophils, lymphocytes, monocytes, eosinophils, or basophils — because each subtype suggests different possible causes.

In extreme cases, counts exceeding 100,000 cells/µL (hyperleukocytosis) can increase blood viscosity and become a medical emergency.

Causes of a High White Blood Cell Count

The causes of a high white blood cell count are broad, ranging from normal immune responses to serious hematologic diseases. They are usually classified as reactive (benign) or malignant (cancerous).

Reactive or Benign Causes

These are temporary or physiological increases in WBCs due to external or internal stimuli:

- Infections – The most common cause. Bacterial, viral, fungal, and parasitic infections can all raise WBCs, particularly neutrophils.

- Inflammation and injury – Autoimmune diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis, lupus, and inflammatory bowel disease often increase WBC levels.

- Stress and physical exertion – Exercise, pain, surgery, and emotional stress can transiently elevate the WBC count.

- Medications – Corticosteroids, lithium, and beta-agonists are known to raise white cell levels.

- Smoking and obesity – Chronic low-grade inflammation from these factors can mildly increase WBC counts.

- Pregnancy and labor – Physiological stress during pregnancy commonly results in moderate leukocytosis.

- After splenectomy – Removal of the spleen causes a persistent, harmless rise in white blood cells.

- Leukemoid reaction – An exaggerated but non-malignant increase (often > 50,000 cells/µL) seen in severe infections or major stress.

Malignant or Hematologic Causes

These result from uncontrolled production of abnormal white blood cells within the bone marrow:

- Leukemia – Cancers such as acute myeloid leukemia or chronic myelogenous leukemia cause uncontrolled WBC proliferation.

- Myeloproliferative neoplasms – Disorders like polycythemia vera or myelofibrosis may elevate all blood elements, including WBCs.

- Lymphoproliferative disorders – Conditions like chronic lymphocytic leukemia or lymphoma cause increased lymphocytes.

Accurately differentiating between reactive and malignant leukocytosis is crucial, as management strategies differ completely.

Recognizing Patterns: Subtypes of Leukocytosis

Different WBC subtypes point toward different underlying problems:

- Neutrophilia – Suggests bacterial infection, inflammation, stress, or steroid therapy.

- Lymphocytosis – Commonly seen in viral infections and certain leukemias.

- Eosinophilia – Associated with allergies, asthma, parasitic infections, or some drug reactions.

- Monocytosis – May indicate tuberculosis, chronic infections, or inflammatory disorders.

- Basophilia – Often occurs in myeloproliferative diseases or chronic allergic inflammation.

A microscopic review of the blood (peripheral smear) can reveal immature or abnormal cells, hinting at leukemia or other serious disorders.

Symptoms and Clinical Signs

A high white blood cell count often causes no direct symptoms. Instead, signs come from the underlying condition triggering it.

Typical symptoms include:

- Fever, chills, or night sweats

- Fatigue or weakness

- Unexplained weight loss

- Bone or joint pain

- Enlarged lymph nodes

- Abdominal fullness (from an enlarged spleen)

- Easy bruising or bleeding

- Shortness of breath or persistent cough

In cases of extreme leukocytosis, blood may thicken, reducing oxygen delivery to tissues. This can cause headaches, confusion, blurred vision, or breathing difficulties — all of which require urgent care.

Diagnostic Approach

When a high white blood cell count is detected, physicians follow a structured diagnostic process to determine its cause.

Step 1: Confirmation

The first step is to repeat the complete blood count (CBC) to confirm the elevation. Clinicians review the patient’s medical history, medications, smoking habits, and any recent illnesses or surgeries that could explain temporary changes.

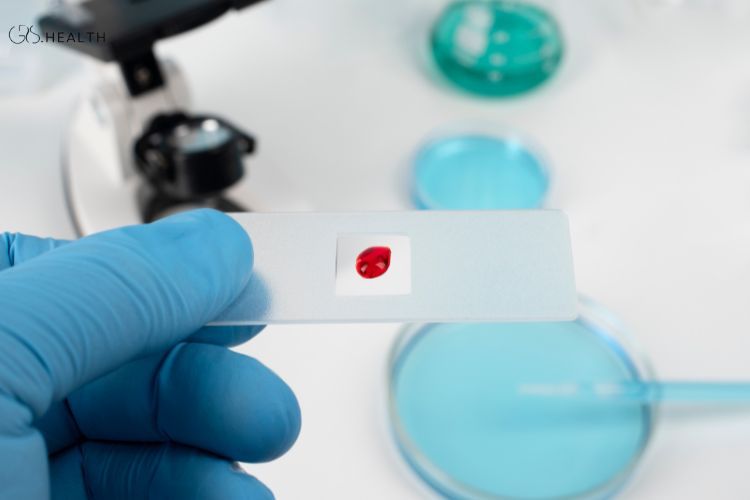

Step 2: Differential Count and Peripheral Smear

A detailed WBC differential identifies which cell types are elevated. Microscopic examination of a blood smear can reveal abnormal shapes, immature cells, or blast forms suggestive of leukemia.

Step 3: Further Laboratory Testing

Depending on initial findings, additional tests may include:

- Bone marrow aspiration or biopsy

- Flow cytometry or cytogenetic analysis (e.g., JAK2, BCR-ABL mutations)

- Cultures and infection screening

- Inflammatory markers (ESR, CRP)

- Autoimmune panels

Step 4: Imaging Studies

X-rays, CT scans, or ultrasounds may be ordered to identify hidden infections, abscesses, or malignancies.

Step 5: Clinical Interpretation

All data are correlated with the patient’s overall condition. A mild high white blood cell count in someone recovering from the flu may be benign, whereas the same result in a fatigued patient with anemia may indicate leukemia.

Implications and Risks

A high white blood cell count itself is not a disease but a sign. The underlying cause determines the clinical importance.

Benign Implications

When leukocytosis arises from infections, stress, or medication, it usually resolves on its own after the trigger is removed. These cases carry an excellent prognosis.

Serious Implications

Malignant or prolonged leukocytosis carries several potential risks:

- Leukostasis or hyperviscosity – Extremely high counts can impair circulation and oxygen delivery.

- Organ infiltration – Abnormal white cells may accumulate in organs such as the liver or spleen.

- Bone marrow suppression – Overgrowth of cancerous cells crowds out healthy red cells and platelets.

- Functional immune impairment – Despite high counts, defective leukocytes increase infection risk.

Therefore, identifying the root cause early is vital for preventing complications.

Treatment and Management

Treatment of a high white blood cell count targets the underlying disorder rather than the number itself.

For Reactive Causes

- Infections – Appropriate antibiotics, antivirals, or antifungals.

- Inflammation or autoimmune diseases – Use of corticosteroids or other immunosuppressants.

- Drug-induced leukocytosis – Adjust or discontinue the offending medication.

- Lifestyle modifications – Quitting smoking, maintaining a healthy weight, and stress management.

- Observation – In mild cases, simple monitoring may suffice.

For Malignant Causes

- Chemotherapy or targeted therapy – To suppress abnormal white cell growth.

- Leukapheresis – A rapid method to remove excess white cells in life-threatening leukostasis.

- Bone marrow transplantation – In selected leukemia or myeloproliferative conditions.

- Supportive care – Including transfusions, antibiotics, and infection prevention.

Individual treatment plans depend on disease subtype, severity, patient age, and overall health.

Prognosis and When to Seek Medical Advice

The prognosis varies:

- Reactive leukocytosis often resolves once the underlying problem is treated.

- Malignant leukocytosis outcomes depend on early detection, treatment response, and genetic factors.

You should seek medical advice promptly if:

- Your high white blood cell count persists or rises rapidly.

- You experience fever, night sweats, or significant fatigue.

- You develop bruising, bleeding, or swollen lymph nodes.

- You have breathing problems or neurological symptoms.

These signs could indicate serious underlying conditions that require immediate evaluation by a healthcare professional, ideally a hematologist.

Summary and Key Takeaways

- A high white blood cell count indicates immune activation or disease but is not a diagnosis by itself.

- Most cases are reactive and harmless, caused by infection, inflammation, or stress.

- Malignant causes like leukemia require urgent investigation and treatment.

- Identifying which WBC subtype is increased gives crucial diagnostic clues.

- Evaluation involves repeat testing, blood smears, and sometimes bone marrow examination.

- Management focuses on resolving the root cause rather than lowering the count directly.

- Most people recover fully once the cause is treated; persistent cases need specialist care.

Conclusion

A high white blood cell count is a common laboratory finding that reflects your body’s defense system at work — but it can also be an early warning sign of a deeper problem. Understanding its significance requires careful interpretation by a qualified healthcare professional, taking into account symptoms, medical history, and test results.

In most cases, leukocytosis is a normal reaction to infection or stress and resolves naturally. However, persistent or extreme elevations may indicate blood or bone-marrow disorders requiring further evaluation.

Monitoring your blood health through regular checkups and maintaining a healthy lifestyle — including adequate sleep, nutrition, and stress management — are essential steps to supporting your immune system. If your doctor reports a high white blood cell count, don’t panic; instead, discuss the possible causes and next steps to ensure timely and accurate diagnosis.

Sources

- Hematology. American Society of Hematology, Malignant or benign leukocytosis

- American Family Physician, Evaluation of Patients with Leukocytosis

- WebMD , What Is Leukocytosis?